My Project:

As I said in the first installment of One Lucky Idiot, my plan is to write, every so often, a post carrying out a kind of cultural analysis of myself. My background, my circumstances, my life events. You know, theorizing myself and putting myself into the larger social context of the world over the past 70 years.

And, yes, I am more than astonished to be 70 years old already...

Again, this project is no kind of memoir or confessional or autobiography. Ugh. Instead, it’s an exercise in exploring where and how I fit into The Regime—that is, the dominant discourses and hegemonic social structures of American society as they shift and renegotiate.

In the first installment of this series, I asserted and explained why I consider myself to be one lucky idiot who was born lucky.

In this second installment, I pick up where I left off.

One Lucky Idiot

Installment #2: Raised Lucky

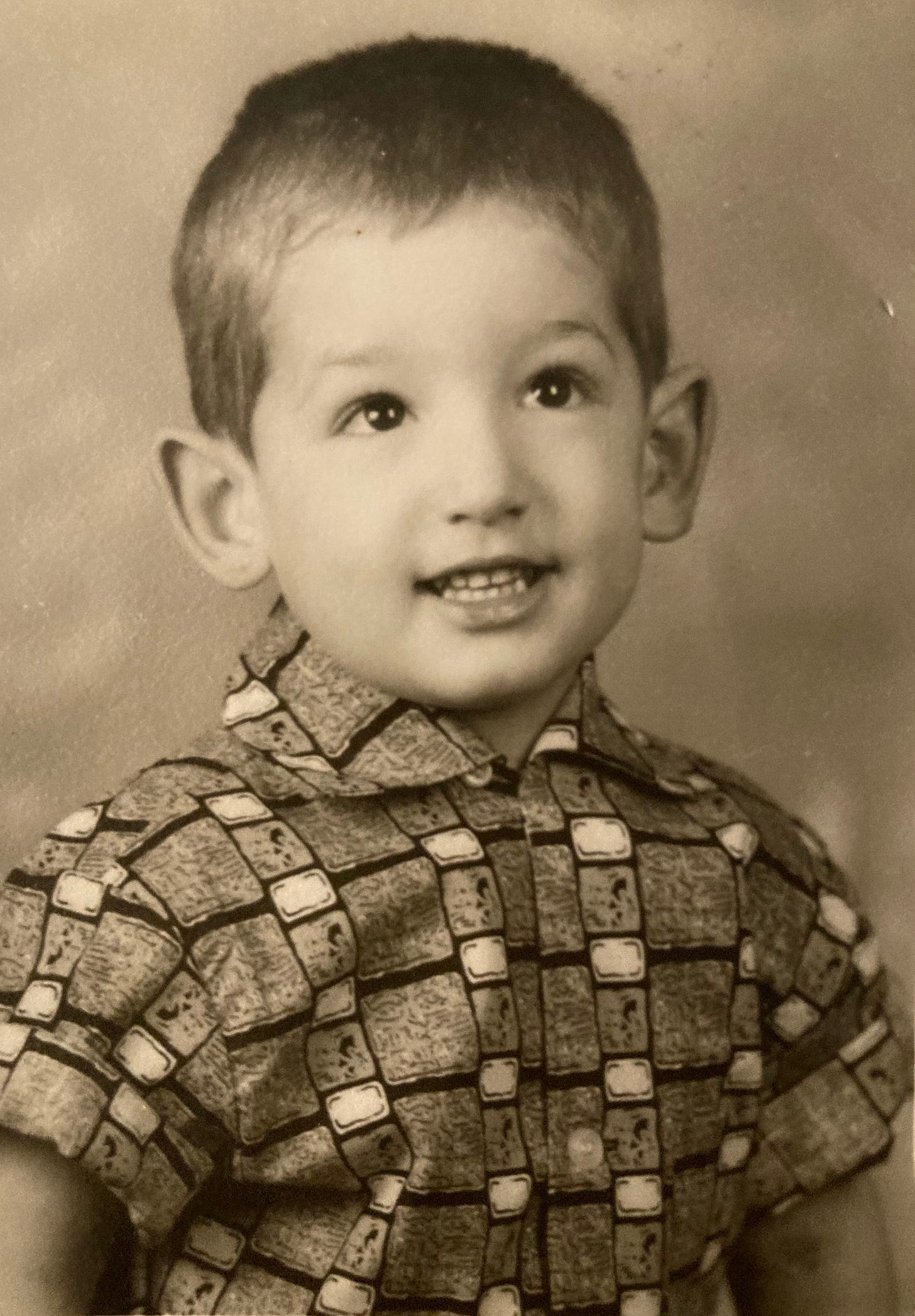

For the first ten years of my life (1954-1964), I was raised in Pocatello, Idaho. Again, at first blush, that may not sound like much of a lucky break in life. But for a little white boy with very large ears, it turned out to be a pretty good Huck Finn-ish existence.

For me, a kid’s life in Pocatello played out on the idyllic side. Starting from Kindergarten, my brother and I could walk ourselves to and from school. I could ride my bike anywhere I wanted. At our first house, we had an apricot tree in our backyard and hanging over the fence was the neighbor’s huge raspberry bush, so summers were one long fruit frenzy. To top it all off, my grandparents lived just down the street. Whenever I liked, I could wander over and enjoy a nutritious treat of Coca-Cola and homemade fudge with Grandma.

In short, the Good Life.

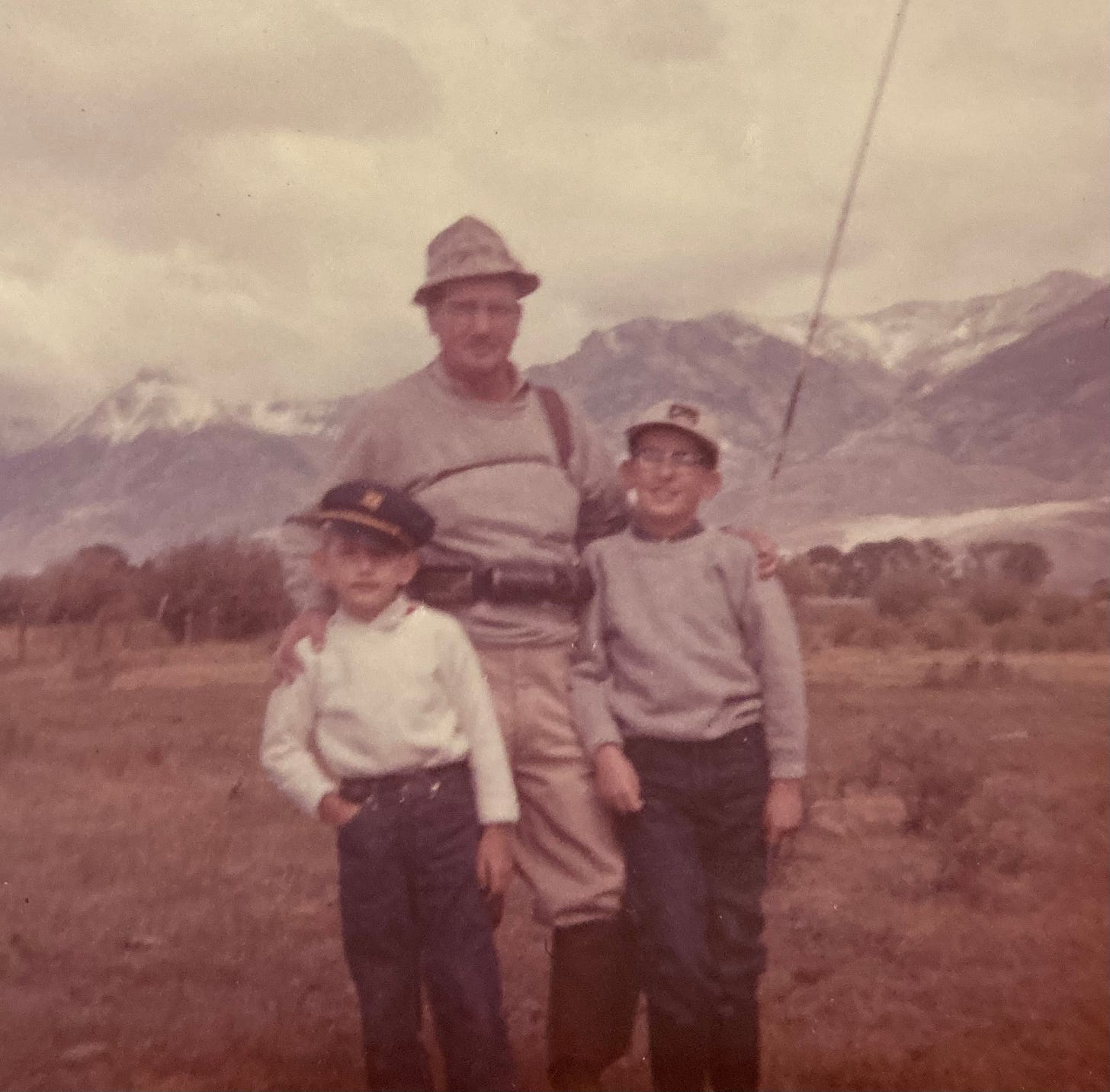

Best of all, from late spring into early fall, every Friday afternoon we packed up the cars and drove north across the Arco Desert “up to fish camp,” as Grandpa called it.

By “fish camp,” Grandpa meant a small patch of land he and a few of his best friends (that is, hunting and fishing companions) leased from a rancher named Keel. Keel’s spread was along the Big Lost River in eastern central Idaho, on the west side of Route 93 as you drive up the long valley from Arco. The turnoff onto the narrow, gravel, seemingly endless access road over to Keel’s ranch—and our fish camp—lay somewhere between Leslie and Mackay.

This is high desert country in the Sawtooth Mountain Range. Country gorgeous as it is dry and stark. Country that’s home to rattlesnakes, antelope, and sagebrush.

In short, Boy Paradise.

Our fish camp had started out as a rough-and-ready tent site just for the menfolk. Soon, however, it began to transform into a small trailer camp. By the time I started going up to camp, there were five or six rigs of various sizes enclosed by a barbed wire fence, to keep out Keel’s cattle. As the years went by, the creature comforts of our fish camp steadily upgraded.

We went from a designated pooping site in the woods to a single outhouse for the whole camp to a well and indoor plumbing. We went from kerosene lamps and flashlights to electricity run into every trailer. We went from small, silver teardrop trailers to bigger travel trailers to—in the case of ours—a long singlewide boasting kitchen, living room, bathroom, and two bedrooms. As I inferred from the menfolk, all of these transformations were required by the womenfolk, so they could come up to camp on weekends, too.

I’m not at all sure that was actually the case. My mother and grandmother seemed perfectly happy roughing it.

One thing I did know for sure, these weekends were the absolute highlight of my young life—and thus the groundwork for my idyllic Idaho boyhood.

Here was my typical Saturday up at camp.

Right before sunrise, Grandpa would grab ahold of my big toe to wake me. Quickly and quietly I’d get dressed for fishing. Trout bite best at dawn. But before we could get out the trailer door, Grandma would appear in her nightdress and robe, insisting I have a bit of breakfast. Grandpa was always itchy to get out fishing, but he knew he couldn’t fight City Hall. So I wolfed down two pieces of cinnamon toast and a mug of hot chocolate while Grandpa gulped a cup of coffee.

He and I would be out on the early morning river for two or three hours. We’d try all the nearby holes to find the one where the big ones were really biting. By the time we traipsed back to camp, everyone else was up. My parents, my brother, and Grandma already making a huge breakfast for everyone. Flapjacks, eggs to order, bacon, and my personal favorite: hashbrowns.

Yup, up at camp, just like a Hobbit, I got to have a second breakfast.

The rest of the day could fall a few different ways, depending on the season. Most of the time we went on a long fishing expedition. We’d pack a sandwich, walk way upriver on the dirt road through the cow pastures, strike onto the river at some point, and spend all afternoon wading and fishing our way back down to camp.

I particularly loved being in the cold water in my hip waders.

Occasionally, we went out hunting mourning doves, which made a fine stew after you plucked out all the birdshot. I was too young to shoot a shotgun, but it was fun watching Grandpa, who was a crack shot. One time he let me drive the Lincoln Continental very slowly down the gravel road while he leaned out the passenger’s side window to shoot. He ended up shooting the hood ornament off the front of the car, though, which was hard for him to explain to Grandma. So I never got to drive the Lincoln again.

Sometimes my brother and I would spend hours exploring the woods around the camp. Often either our mother or father would join us. We took to calling these sweet-smelling stands of trees by the river “the balsam woods.”

Dinners at camp were always a grand affair. A huge fish fry at a long picnic table. Often there was a total of 15 or 20 people up at camp. (My brother and I were always the only little kids there, so we had lots of undivided adult attention.) After dinner, at sunset, Grandpa and I would grab our poles and sneak down to the river again. This time to try our hands at fly fishing. Trout go for a fly best at evening time.

We’d cast out and slowly reel in our flies on the faster parts of the river. Just on the edge where the riley water smooths out. I was still too young to be much good at catching trout on flies. I had a hard time recognizing their bite, then I wasn’t quick enough to jerk my wrist to set the hook. Grandpa, though, was an expert fly-fisherman.

Finally, nighttime at camp was spent with everyone sitting around a blazing campfire. Fish stories getting told, whiskey (or hot chocolate) getting sipped, jokes and gossip getting shared, and the billion or so stars overhead getting stared up at.

Come Sunday afternoon, everyone reluctantly packed up cars and drove the 100 miles back down to Pocatello for another week of work or school.

Yes siree. Huck Finn had nothing on me.

But...

But let’s face it. While I was growing up living my idyllic Idaho boyhood, there was a lot of shit hitting the fan around me. Shit I was never even aware of at the time. While most kids grow up thinking that their family life is “normal”—that is, everyone lives this way—I see now how my early upbringing took place in what can only be characterized as a bastion of white supremacist middle-class patriarchy.

During my 10 years in Pocatello, we lived in three different houses, each one a little bit nicer than the last. I know now that my father was working his way up the corporate ladder. Meanwhile, my mother, like it or not, was working fulltime—unpaid—at home. While in Pocatello, I never encountered or heard of a family arranged any differently from ours.

Idaho was also blindingly lily-white back then. (News flash: Idaho is still over 80% white.) So, as a kid, I knew nothing about racial issues. Looking back, I realize now that I never went to school with a kid who wasn’t white until the 5th grade. That year, there happened to be two black kids in my class. Gregory Hines and Len Liggins. Both nice guys who, I would guess, wound up in Pocatello because at some point their fathers worked as Pullman porters for the Railroad.

I also realize now that my grandparents routinely used a racist phrase. They would refer to something—like the night sky or the color of a car—as being “blacker than Toby’s ear.” As a kid, I never understood exactly what they meant by that. (But I did wonder who this Toby guy was.) Years later I figured out the casual racism of their remark.

Neither did I ever go to school with a kid of Asian descent. We did frequent a really good Chinese restaurant run by a “right fine Chinaman,” as my grandfather would say, named Bing. So there was a significant Chinese population in Pocatello, again, because of the Railroad. But I never went to school with any of the children.

Similarly, there was a Japanese population in Pocatello. This time not because of the Railroad, but because their families had been imprisoned in Idaho internment camps during World War II. In fact, my grandfather did a lot of business with someone he quite pleasantly referred to as “Jim the Jap.” This man owned a body shop that my grandfather, as a car mechanic, routinely sent customers to because Jim did such good work. Grandpa even routinely took “messes of fish” we caught up on the Big Lost River over to Jim and his family because “those people sure do like their fish.”

Again, oblivious racism on the part of my grandparents and, for some reason I still don’t understand, I never went to school with a fellow student who was Japanese-American.

As for Native Americans, well, such folks were invisible in Pocatello—even though the city is named after an indigenous Chief. Just west of town is the 800-square-mile Fort Hall Indian Reservation. Since 1868, this Reservation has been the compulsory home of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes (today numbering a little over 5,000 people). The history of their treatment by European settlers features, needless to say, severe discrimination, massacres against them, roundups and forced marches, lies, land poaching, pollution by local industries, and innumerable broken promises.

Unsurprisingly, not only did I never go to school with a Shoshone-Bannock classmate, but I never even saw a Shoshone-Bannock child or woman in my ten years living in Pocatello. Every once in a while, on the streets of downtown Pocatello, I’d catch a glimpse of what my grandparents called a “young Buck.” That is, a man in his twenties or thirties come into town off the Reservation for a day to look for work (that he was never going to be given) or, more likely I was told, to seek alcohol. A few times, even I could tell that these young men were drunk, either visibly reeling or passed out on the sidewalk.

Two well-known Pocatello “characters” of this type were Timmy Tapioca and Weasel Wildcat. I don’t know if those were their real names or just what the newspaper had dubbed these so-called “troublemakers.” I spotted the notorious duo a time or two. All they looked like to me was stoic and rumpled.

As a big-eared white boy enjoying his Huck Finn-ish existence, I didn’t have to know about any of these matters.

Three Really Lucky Breaks

Finally, along with all the other good fortune that landed in my lap, three really lucky breaks befell me during my Idaho childhood.

Really Lucky Break #1: I was not raised in a religious tradition.

Thank God.

My mother’s family was Mormon. In fact, I’m a descendant of William Clayton (1814-1879), who was something of a big deal in the early Mormon Church. Along with Brigham Young, Clayton helped trailblaze the Mormon trek west from Nauvoo, Illinois to Salt Lake City, Utah. In Illinois, Clayton had worked closely with the Mormon founder (and likely nut-job), Joseph Smith—that is, before Smith was killed by an angry local mob. William Clayton is most famous for keeping a detailed diary of his time with Smith as well as composing the beloved Mormon hymn, “Come, Come, Ye Saints.”

So, as you can see, I was well set up to become a Stormin’ Mormon—western vernacular for a devout follower of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Happily, though, well before I was born, my mother’s family had turned Jack Mormon—western vernacular for folks born into the faith but not particularly believing in or following any of its odd tenets.

As chronically underpaid working folks, my great-grandparents and grandparents did not see the wisdom of tithing to the Mormon Church. Nor did the Mormon practices of wearing secret underwear or not drinking coffee or cola especially appeal to them. As a result, thankfully, I was never hauled off to Mormon rituals at the local Ward. Nor was a two-year Mission ever in my future.

Don’t get me wrong. I’ve encountered many, many Mormons who are perfectly lovely folks. You bet. I’ve just never wanted to be one of them.

Equally non-religious was my father’s family. They were recent immigrants (one generation back) from the Swiss-Italian region around Turin, Italy, but their origins were French Huguenot. Maybe, as a family, they’d experienced enough persecution themselves back in the Old Country to put them off wanting to be overly devout about their Protestantism in the New Country. I don’t really know. All I do know is that the only churchgoing I had to suffer through as a kid was the occasional Easter Sunday Service at a very milquetoast Methodist congregation.

And all we did there was sing way too many hymns.

Again, not to offend churchgoing folks, I think it fortunate that, as a youngster, I didn’t have any kind of absolute belief system pounded into my head. This spiritual dearth left well open my intellectual curiosity.

Really Lucky Break #2: I was raised in a family that practiced and valued humor.

Thank God.

Humor is one of the best teachers for a kid. As you grow up, humor serves as an introduction to the adult world—its complications, its subtleties, its contradictions, its frequent absurdities. Done well, humor is basically insight.

Humor is also fun. And fun is very good for a kid. Fun relaxes you. Fun opens you up to possibilities. Fun helps you cope.

In my experience, humor and fun are magic elixirs of instruction and delight.

Mainstay humor in my family were wry quips, witty observations, wordplay, repartee, momentary flights of screwball imagination, and the occasional spontaneous practical joke.

For example, one time up at camp, after driving along a long gravel road, the car’s windshield got caked with dust. When we stopped before pulling out onto the paved road, Grandpa hopped out of the driver’s seat to wipe clear his side of the windshield with a chamois cloth. Then he walked around to the passenger’s side, where my Dad was sitting. There Grandpa etched out just two little peepholes. With a straight face, he got back in the car and we drove off. We didn’t get far before everyone burst out laughing.

Fair game for our humor was folly and pomposity of any kind and from any quarter. (Public figures, bad movies, silly TV shows, anyone wielding a bit of petty power too gravely.) We never engaged in put-down humor. Too corrosive—and not really humor. (Put-downs are expressions of resentment and self-doubt.). Nor did we punch down with our humor, aiming jokes at the less fortunate. When punching at all, we preferred to punch up.

Most important, irony was in great supply.

What better education than learning to recognize and appreciate irony? The adult world is awash with people saying one thing but meaning the exact opposite.

Used jokingly, irony presents a delightfully intricate humor puzzle to unravel, often with a delicious bit of acumen at its core. (E.g., Facts have a liberal bias.)

Used seriously, irony becomes bullshit. (E.g., Mexico is going to pay for the Wall.)

Sorting sense from nonsense is a vital act of adulting. I count myself lucky to have been raised in a family culture of thought-provoking banter. As I grew up, it kept me both grounded and on the ball.

Really Lucky Break #3: my family moved Back East when I was ten years old.

Thank God.

In 1964, my father’s company decided to transfer him to its corporate headquarters in New York City for some career training. This move turned out to be big breaks for us all.

Both of my parents desperately wanted to break out of the social confines and small-mindedness of Idaho. They had dreamed of it, I think, since they were kids.

My grandparents certainly were upset (and my grandmother livid) with my father for “taking away the grandkids back east.” But my mother (to make matters worse, an only child) certainly was eager for the change. Somehow, so were my brother and I. Somehow, even as kids, both of us intuited the importance of this adventure. The golden opportunity it offered.

This was our chance to escape Idaho.

I don’t know how we knew that. But I’m lucky we left when we did. Don’t get me wrong. I love my home state. I love my boyhood there. I love the feel of high desert altitude. The dry smell of sagebrush. Deep snow and thick pines on severe mountains.

But I mourn what the state of Idaho has become—or maybe always was. And I shudder to think what such grotesque bigotry might have done to me over the years.

COMING IN TWO WEEKS: as my grandfather always said, “We’ll just have to see...”

AND DON’T FORGET...

Read some provocative fiction. Check out and subscribe to my other Substack newsletter, 2084 Quartet at:

While you’re at it, read some provocative social commentary. Check out and subscribe to this absolute Substack gem as well:

I LOVE THIS!! So descriptive and insightful.

I can smell the sagebrush and hear the fish frying.

So elucidating!!!!